Even in early May, the sun can be strong and the day’s heat harsh. The desert is full of warning, and I always remain a little on edge. But if I squint my eyes, I can see the fuzzy ocotillo as underwater flora gently undulating, with the canyons as nests for octopi and other bottom dwellers.

West Texas used to be a seabed. During the Permian Era, around 250 million years ago, all of the continents remained fused as Pangea and the surrounding sea levels were shallower. The three areas of large Permian deposits and fossils are now in far-flung corners of the earth – the Ural Mountains in Russia, an area of China, and West Texas’ Permian Basin. The sea above us was tropical and teemed with life, and the giant 400-mile Capitan Reef remains a beautiful example of an ancient marine home. This reef, exposed due to subsequent faulting, today includes Guadalupe Peak and the surrounding park, and is the highest point in Texas.

We are in the third year of an extreme and continuous drought, something not seen since the 1930s in El Paso. Last summer saw more than 70 days of extreme heat above 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and this spring experienced record dust storms. Bone-dry heat can feel good. It heals the lungs. It relieves arthritis. It also chaps our skin and leaves our mouth and eyes dry. It can suck the last drops of moisture out of living bodies and leave behind beautiful mummified creatures and fossils.

Desiccate. That is what the desert does. This word also means to take away energy and passion, to leave one hollow. Sometimes I feel that from the desert too.

But it is now spring in El Paso, and despite the lack of rain, the cacti are in bloom and the mesquite trees are a neon green with their new growth. When you are on the seabed, in an arroyo, running up a trail, it is as if you were in a Technicolor movie in the early morning light. From above, things look gray and brown, but from below it’s a polychromatic marvel.

Once when I told a friend from Beijing that I was from El Paso, he said that his visual impression of my town was that of a tumbleweed gently rolling down a wide dirt road. He was unaware of any plant life in the desert. Yet the visual symbolism of the tumbleweed is misleading. We see the hollowness of a plant dislodged from its roots, subject to the whims of a breeze, its journey impeded by fencing and other objects. Yet even the tumbleweed still scatters its seeds as it makes its final death journey. As it splinters and dissolves, the tumbleweed spreads itself far and wide to propagate. It is not barren.

If you drive through Interstate-10, the Franklin mountains appear bereft of any significant vegetation. Ocotillo are actually not cacti, but a flowering shrub that goes through periods of losing its leaves. We don’t have the impressive cactus forests of Sonora or Baja California, the Seussian giants that tower over you.

Yet it’s all there at our feet. You have to experience the Chihuahuan Desert on foot. There are tiny treasures, some the size of a penny. Pincushion, button, hedgehog, barrel, and the cholla we use for firewood in the summer. There are flowers that open only in the moonlight, attracting the night pollinators. Daytime blooms erupt in fuchsias, oranges, yellows, dazzling the flying creatures, telling us we may look and admire, but not touch. We are the largest and most biodiverse desert in North America, with more than 3,000 plant species and nearly 500 cacti species, or a third of the world’s cacti.

While lechugilla is the biomarker of this desert, the nopal or prickly pear is probably the most essential cactus to wildlife and humans from this region. All parts are edible and provide sustenance and liquid to rabbit, deer, javelina, rodents, birds and bees. Because they are so easy to propagate, people bring you different varieties as gifts. You simply stick a pad in the ground, and it takes root. Thanks to Rob, Jaime, and a worker from San Luis Potosí who brought me the thickest pads for nopales. My neighbors ask to harvest the tunas in the late summer, when they turn a deep purple shade. We carefully pull them off with gloves, and the birds descend to pick at the pieces of fruit that are rotted or torn. Last summer we learned how to make jelly with the tunas, with simply cheesecloth to strain the spines. Or as we say in the game Loteria, Al que todos van a ver, cuando tienen que comer, El Nopal!

My husband is also interested in the spirit, the life force of the cactus, as it is used in alcohol, and has spent years traveling to vinatas and small towns making cactus spirits throughout Mexico. On one of our first dates, he took me to the old location of the Arbolito in Juarez, to try the licorice/celery flavor of chuchupaste. Our kids have seen roasting fire pits cooking sotol piñas outside of Janos, and backyard stills dripping trails of bacanora in Aconchi. Many of the cactus spirits are not regulated, still made semi-clandestinely. When we married, we planted this sotol cactus in our front yard, along with the pomegranate and apple trees.

In many ancient desert communities in the world, populations were nomadic. They had to be. The Mescalero Apache tribes of this region were named after their staple food, mescal (the agave plant), with which they made a hard-tack paste from the piña that was roasted, ground and dried. It was harvested in the spring when the sugar content was highest, and was highly transportable and nutritious. Mescal played an important ceremonial part in tribal life; the long preparation process was a communal project. The winter following our marriage was icy cold, with a three-day hard freeze where the temperatures didn’t top 3 degrees Fahrenheit. That following spring, as the temperatures warmed, the blue agave in our front yard all began to melt, like a Salvador Dalí painting, and then they began to rot, their fermented smell wafting onto our front porch.

This past January, I was in Dublin, trying to keep four little boys warm on the way home from the park in Glasnevin. The days were short, and the light weak. Everything about the climate is different from El Paso. My brother lives near the Botanic Gardens, and I’d walk through different parts each day – ancient Irish forests, rose gardens, Japanese rock arrangements under the magnolias. There is a large glass conservatory, and we’d go inside to huddle into the humid warmth. I smelled the humus and peat, and then I saw them. A wide variety of cacti through a glass door, in a room at the far side of the greenhouse. Fouquieria splendens. Echinocereus pectinatus. Opuntia engelmannii. Ferocactus wislizeni. Cacti are regulated worldwide under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which seeks to protect and conserve. It was like entering a museum from the future or from another planet... While the kids played hide-and-seek near the banana tree and tropical huts, I strolled in circles around the cacti room, thinking of home.

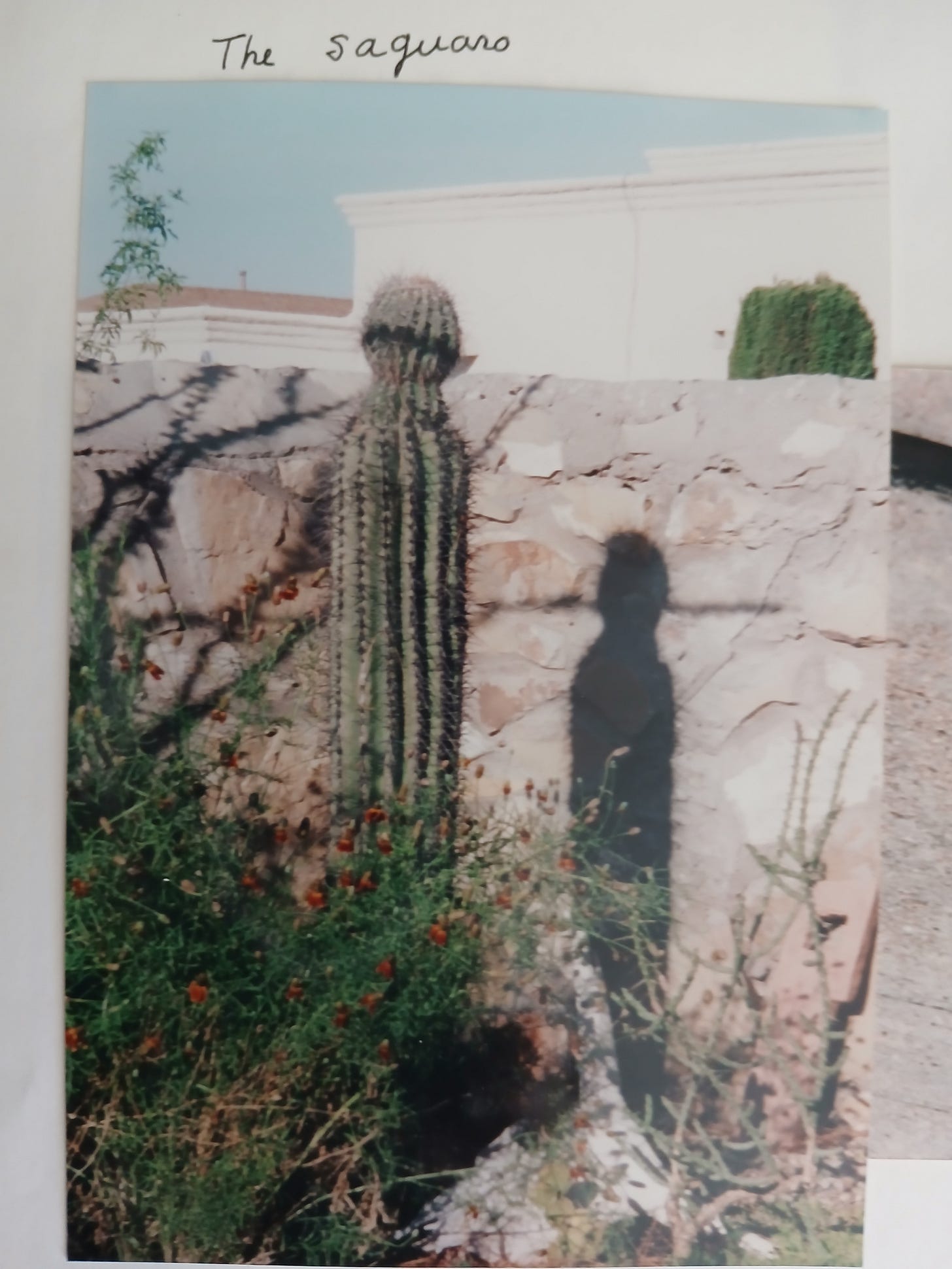

I was perhaps ten years old, and the scream barely interrupted my reading. It was a languid summer afternoon, and I concluded there must be ants, or perhaps a scorpion. But another minute passed, and my brother rushed in, crying, “She needs help!” My mother, in her gardening, had fallen from the wall onto our Saguaro cactus.

The stately Saguaro that we had planted when we moved to a new house; hopes of a piece of Arizona in our yard, but which had yet to grow one millimeter, much less the quintessential arm.

Lying on the bathroom floor, shaking as she showed me her forearm, long cactus spines protruded, leaving only trickles of blood, but the poison that ensured its survival for centuries, coursing through her veins. Tweezers, rubbing alcohol, a bit later we were laughing, and it was the end of a crisis.

August arrived and my mother walked through the cactus garden, stopping only to see the smooth silhouette broken by new growth of nearly three inches. Not even the late afternoon sun could hide the hump’s dark red hue, and the sanguine leer of the long new spines. The saguaro had sprouted a head, appearing almost the height of my mother as it was planted behind the pink wall. A lizard rustled in the undergrowth, and the turtles came out for crepuscular insect hunting, but the two figures remained still, each coolly regarding the other with a little more respect.

My coauthor and friend brought me a shell and stone embedded with fossils from her hikes in the desert of NW El Paso county. Wishing for more water now.

I lived in the high desert of New Mexico for over 30 years. You expressed it all.❤️